EDUCATIONAL MATERIAL

Pluralism in qualitative research

Common features of qualitative studies

Main steps in designing qualitative research.

Formulating research questions

Determining the research setting.

Choosing methods of data generation

Evaluative criteria of qualitative research

Critique of qualitative research

Ethnographic research –Fieldwork by Participant Observation

Types of ethnographic studies:

- How to do ethnographic research-some practical suggestions

- Steps in conducting ethnographic research

- Criteria for evaluating an ethnographic design

- How to take notes

- Ethnographic Interviewing

Introduction to Social Research

Learning outcomes

By the end of this chapter students are expected to:

- have an awareness of social research and why it is undertaken;

- understand the benefits of generating knowledge through scientific inquiry as compared with knowledge based on personal experiences;

- be able to distinguish between basic and applied research;

- have familiarized themselves with three main categories (or levels) of social research, namely exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory;

- have developed an appreciation of the philosophical underpinnings of social research, especially the opposing paradigms of positivism and postmodernism;

- understand the organic relationship between research and theory, as well as the processes of inductive and deductive reasoning;

- differentiate between quantitative and qualitative research approaches;

- begin to critically appraise the ideology and ethics of research, and their dynamic (changing) nature.

Introduction

This chapter is an introduction to empirical research in the social sciences. It starts with conceptualising research as a natural process of human learning about the world. It then goes on to differentiate this type of everyday life research from the so-called “scientific method” which is based on specific standards agreed upon by an international community of researchers. The chapter proceeds with explaining the difference between basic and applied research, with special reference made to action research. Next, it discusses how social studies may differ in the depth (or level) of understanding they seek to attain and distinguishes between exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory research. The chapter also analyses the relationship between research and theory, highlighting Wallace’s circular model of science which includes an iterative process of inductive and deductive reasoning. The philosophical foundations of research are then explored, focusing on the paradigmatic stances of positivism and post-modernism. Finally, the chapter ends with a discussion of quantitative and qualitative research methods, which are defined on the basis of the types of data they generate and use.

Research and the “scientific” method

From the moment we are born, we, humans, have an innate drive to discover and understand the world in which we live. The desire to learn about, and create knowledge of, our world is almost instinctive. But how is such knowledge generated? This is done through naturally observing our environment in our everyday lives, generating information (data) which we then analyse using our innate cognitive capacities to identify patterns of what happens, how it happens, and why it happens. By patterns, we mean “phenomena that occur repeatedly in life” (Walter, 2019, p. 8). Such knowledge helps us predict what will (or may well) happen under certain circumstances and decide how we should behave to have desired outcomes. This systematised – yet natural – process of knowledge generation constitutes what is known as “research”, seeking to answer questions of three main types: “what”, “how” and “why”? The first aims to describe “what is” or “what exists”, the second focuses on the way something happens, and the third seeks to explain why something happens (looking for the causes behind it). This is a process in which people engaged long before sciences (such as physics, anthropology, sociology, etc.) were established.

Let’s take a familiar example (Figure 1.1). We often see babies dropping their food over the highchair table, watching it hit the floor with delight (to the dismay of their infuriated mother who spent the whole morning preparing their favourite meal…). They often do this to discover how different food items or cutlery (of varied shapes, weights, or substances) produce different outcomes as they reach the floor. These are spontaneously planned experiments that systematically generate data which babies analyse (albeit unconsciously) to reach certain conclusions or generalisations, such as “heavy items will be loud when they reach the floor”, “glass objects may break on the floor”, or “when my soup falls on the carpet my mum starts panicking”.

Even though the above example may bring to mind the well-defined and highly structured experiments that quantitative researchers conduct, everyday research is often far less discernible and more organically embedded in daily activities. Let’s think of what happens when we join a new work setting. In the first days or weeks of taking up a new post, we are likely to feel hesitant about our actions, spending much time just observing the behaviour of, and language used by, our colleagues in an attempt to identify what (unseen) norms guide their interactions, what is that they value the most, and what sense (understandings) they make of their work. Such observations generate data which help us learn the culture of this (new to us) work setting and adapt our behaviour accordingly to become accepted members; we may work out how and when to be formal or informal, when to be serious and when not, what constitutes humour, the relative status of different people, new technical terms or commonly used turns of phrase, etc.[1] (Holliday, 2016). This natural exploration of a new culture resembles the rather flexible, unstructured, designs of qualitative research in which it is often difficult to distinguish the act of “researching” from that of actually “living in” a field (as happens, for example, in ethnography).

Having explained what research is, a reasonable question that may arise at this point is the following: if doing research is part of human nature, what is, then, so special about the “scientific” method? In fact, if we were to determine the primary components of the research we do in our daily lives, we would (most likely) realise that these make part of the very definition of “science”, namely: (a) it is a focused process (it has a purpose), (b) it is empirical (based on real-world data collected through experience), (c) it involves the analysis of data to make generalisations, (d) it attempts to explain such generalisations (i.e. builds theory), (e) it is based on logical thinking, (g) it is systematic (follows specific steps in a sequence, even though these may not be explicit or obvious to us) and (e) it accounts for existing knowledge (e.g. in our previous example, the new employee may ask another coworker if s/he thinks it would seem “disrespectful” to call their boss by their first name in order to check if his/her own conclusions agree with those of others who have worked there for longer) (Adler & Clark, 2015; Punch, 2005, Black, 2019).

So, is all research “scientific”? The answer is “yes…and no”. Walter (2019) aptly observes that a core defining feature of the scientific method is its agreed character. For our research to be considered “scientific”, it must adhere (in all its phases) to specific standards agreed upon, and shared by, an international community of established researchers. Acceptance of, and adherence to, these standards must be made explicit by the researcher, and this is what sets scientific research apart from everyday research or other ways of learning about the world (e.g. vicarious experiences, expert advice, introspection, etc.). These standards have multiple layers of detail and may differ between disciplines or schools of thought, yet they define some universal guidelines:

- Careful formulation of research aims and questions (Adler & Clark, 2015).

- Having an explicit structure. What is meant by “structure” is knowing what the different parts of the research are, how they connect with each other, and in what sequence. This does not imply that everything (e.g. research questions, data collection methods, analysis techniques, etc.) must be worked out in advance. Many research projects adopt loose designs in which the structure gradually unfolds as the research progresses (as happens in ethnography). What is important is that structure becomes explicit at some point between the start and the completion of a project (Punch, 2005).

- Explaining the reasons for our choices: (a) why is our topic worth investigating and (b) why we believe that our chosen methods are a good fit for our research questions (a central criterion for the validity of research) (Punch, 2005). For example, it would make little sense to use self-completion questionnaires to examine toddlers’ experience of a childcare programme (they are unlikely to know how to read or write), whereas observing their behaviour during the programme would be a more suitable approach.

- Sceptical re-examination of our own conclusions: the scientific method requires that the researcher is always cautious about their findings, actively searching for counterevidence against their own claims, and open to the possibility that others may challenge what initially appeared as “rock solid conclusions”. A basic assumption is that no statement can be proven beyond any doubt; between facts (data) and results always lies “interpretation” (Gannon, 2004; Black, 1999).

- Transparency and replicability: this refers to the clear and open (honest) communication of the methods and procedures used to obtain results so that the same research can be replicated under identical conditions by other investigators who wish to verify the findings (Bakken, 2019).

- Publication: scientific research is expected to be published in recognised journals after being reviewed (assessed) by other scientists in the field. It thus becomes subject to public scrutiny, whilst a knowledge base is created which is accessible to future researchers and provides a foundation for their projects (Walter, 2019).

- Adherence to ethical principles that protect the subjects of research from undue harm and, in the case of human participants, ensure that they freely give their informed consent before they are included in a study (Walter, 2019).

- Drawing on a set of “tried and tested” methods for the collection and analysis of data. This does not mean that researchers are expected to apply predefined methods precisely, as these are described in textbooks, but that they craft their own approach by adjusting those methods to the particularities of their study (Jensen & Laurie, 2016).

- Making the familiar strange: this refers to the process of de-familiarising everyday things we know well and take for granted. Putting oneself at a reflexive distance from the object of a study is a key feature of the scientific method, as it is difficult to see things clearly from within a context or situation. The popular saying “culture is to humans as water is to fish” describes how the most essential things in life can be difficult to see and articulate. A fish lives its entire life in water, without necessarily seeing it or even realising its existence. Researchers must make a conscious effort to adopt the position of a stranger in the contexts they choose to study to be able to explore reality with fresh eyes without overlooking things they take for granted or (unconsciously) focusing on data that support their preconceptions. This reflexive approach is necessary in all types of research, but particularly so in qualitative research ( in the study of culture) (Holliday, 2016).

Having explained what is special about the scientific method, it becomes apparent that a key feature of this type of research is that it is extensively communicated within a community of “experts” who assess and scrutinize it based on agreed criteria to ensure “rigour”. Jensen and Laurie (2016, p.30) describe such intracommunity communication as a “collaborative way of creating knowledge” that involves “researchers critiquing and building on each other’s work”. Members of this community are theoretically of equal status, yet, in practice, hierarchies do exist (either visible or hidden) with those accumulating most power promoting certain types of research – through disproportionate funding or publishing – that (unilaterally) serve specific interests. This reflects the political nature of research which is further discussed later.

What is social research?

If research is the systematic search for answers to questions we ask about the world, then social research is concerned with questions about the social world, that is, about people and their behaviour in a social context. This broad category of research includes topics in varied fields, such as psychology (which focuses on the individual’s mental characteristics and how these affect behaviour), anthropology (which studies human cultures across time and space) or economics (that focuses on the way people produce and exchange goods or services) (Punch, 2005).

Researching the social (constructed) world is often more complicated than researching the physical world. Social phenomena are not stand-alone events; they are interwoven with human belief systems and different people may understand these in completely different ways. That is why social research does not only aim to identify social patterns (and explain these in a supposedly “objective” way) but also seeks to uncover the social meanings embedded in these patterns. “Social meanings” refer to the way people make sense of, and understand, aspects of their social lives. Such understandings differ between individuals, groups, or cultures, and therefore, social phenomena cannot be truly comprehended if such sense-making is not taken into account (Walter, 2019). For example, in the so-called “western” or “westernised” world, children working to make a living can be viewed as a factor of inequality (at the very least) or even as a form of abuse. On the other hand, in non-western societies, it can be a respected and valued way of contributing to the maintenance of one’s own family or community. Such contribution is often a source of pride and fulfilment for children in those contexts rather than being considered a symptom of oppression as happens in the so-called “liberal” and deeply individualistic societies of the West (Punch, 2004).

Walter (2019) outlines some further particularities of doing research in the social sphere:

- Interaction and communication with human participants are key elements of social research. Effective people skills are, therefore, essential for social researchers, such as ease in verbal and written communication, active listening skills, and ability to relate to, and show genuine interest in, others.

- Ethical constraints are much more intense in research with humans than in other types of inquiry. Such ethical constraints work towards protecting human participants from undue harm and include the challenging requirement that informed consent must be gained before any participant can take part in a study. Despite the absolute and undebatable importance of such a principle, it can clash with method selection, creating issues of validity and/or reliability, and may even lead to the cancelation of a research project.

- Human participants are not always predictable. Although researchers may ask simple and straightforward questions, respondents can be dishonest or ambiguous in their answers. People are not always prepared to be frank in discussions about their behaviour, attitudes, or beliefs. They may over-report “good behavior” and under-report “bad behaviour” so as to be liked and accepted by others. It would not be surprising if, in a study of drug use, researchers found a discrepancy between participants’ self-reported frequency of smoking marijuana and the recorded number of hospitalisations as a result of consuming it.

- Unlike inanimate objects, people are usually aware that they are being studied. Hence, they develop feelings and attitudes about being studied, which can, in turn, influence research outcomes. More than often, results are affected by participants’ interpretations of what a study is all about and the value they attach to it.

Purposes and levels of social research

We earlier described social research as a systematic process of discovering, and gaining deeper understandings of, the social world. It is often conducted out of a sense of curiosity about the unknown or due to an inner need for shedding light on one’s personal experiences. Research, in this case, has as sole objective the generation of knowledge for knowledge’s sake and is known as basic research. Basic research contributes to the creation of new, or the refinement of existing, theories that explain social phenomena, that is, how and why people behave, interact, or organise themselves in the ways they do (Turner, 1991, as cited in Adler & Clark, 2015). Such theories may not be of immediate practical benefit (such as offering solutions to existing problems) yet they form a foundation of knowledge on which future practical developments can be based (Black, 1999). For example, many businesses of today develop innovative strategies of staff motivation based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs which is a widely known theoretical model developed decades ago (Northouse, 2016).

On the other hand, there are studies conducted with action in mind, aiming to produce knowledge that is used immediately to inform the practices of individuals, groups, or organisations. As opposed to the idea of inquiry for its own sake, this type of research is triggered by a specific practical problem or question and its whole purpose is to lead to action that solves this practical problem or answers this practical question. For example, a school may decide to conduct a study on the learning preferences of its students in order to inform its curriculum planning for the following year. This type of research is known as applied research. Even though applied studies often have a theoretical foundation, their central focus is on enhancing a real-world process, outcome or service (e.g. teaching practice or student performance) rather than refining a theoretical model or explanation (Punch, 2005; Black, 1999). Applied research includes, among others, action and evaluation research (Adler & Clark, 2015).

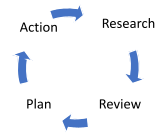

Action research is often treated as synonym for applied research. Yet, it would be more accurate to consider it as one type of applied research. What sets action research aside from other applied research designs is that (a) it is far more situational in nature (focused on the practices of specific individuals or groups in specific contexts), (b) it does not clearly separate the researcher from the researched (those who live in the context are often those who conduct the study), and (c) it follows a cyclical path that reflects people’s tendency to work towards solutions to their problems in cyclical (iterative) ways. For example, a collaborative community project aimed at addressing teen depression in a poor suburban district could be classified as action research, whereas a study conducted by university researchers to develop a new treatment for teen depression with a wide scope of applications worldwide is applied (but not action) research (Jensen & Laurie, 2016; Sarafidou, 2011; Punch, 2005).

Figure 1.2. presents the four main phases of the action research cycle. To illustrate how it works, let’s take an example. Let’s say an archaeological museum wants to better understand visitors’ experiences so as to identify changes that can be made to improve these. For this reason, a research team is set up (composed of staff members and patrons) to design and conduct a series of focus groups with different types of public visitors and to analyse the data generated. This is the first “research” element in the action research cycle. The team then presents results to other members of staff so that they review, together, what has been learned from the study and its implications for practice (this is the “review” element in the cycle). The next steps include creating a change plan for improving visitors’ experiences in the museum (the “plan” element in the cycle) and trying it out through implementation (the “action” element in the cycle). The cycle can start again if the museum wishes to undertake further research, with new focus groups, to assess how visitors respond to the changes made, review results, and inform new planning for new further action, and so on. As Reinharz (1992, as cited in Punch, 2005, p. 138) points out, action researchers “intervene and study in a continuous series of feedback loops”.

Figure 1.2. Action research cycle (Jensen & Laurie, 2016)

The cycle need not start with research; it can start at any phase. For example, the museum may decide to start with action by implementing a new “Augmented Reality” programme which is then followed by research evaluating its impact on the quality of visitors’ experiences. Alternatively, it can start by reviewing existing knowledge on how museums can stay relevant and attractive in contemporary cities before developing (planning) a new programme for attracting a wider range of ages, which will then be implemented (action), subsequently evaluated (research), and so on.

Evaluation research is a type of applied research that aims to assess the effectiveness of certain actions in specific contexts; it seeks to determine whether (or not) the initial objectives or intended outcomes of particular interventions or change initiatives have been achieved, how, and why. For example, an evaluation study might assess the effectiveness of a peer education programme implemented in a secondary school to improve students’ writing skills by organising them in small ‘alike’ groups in which they help each other produce different types of text (Jensen & Laurie, 2016; Adler & Clark, 2015). In fact, evaluation research could also be seen as the “research” element in an action research cycle, seeking to appraise a specific “action”.

Social research can also be classified according to the depth (or level) of understanding it seeks to attain. Hence, a study may be exploratory, descriptive, and/or explanatory (Walter, 2019).

Exploratory research focuses on a relatively under-researched, or completely new, topic so that the researcher gains familiarity and develops some initial ideas about it. It relies heavily on generating “thick” empirical data of a qualitative nature rather than on structured quantitative measures that presuppose the existence of some theory or conceptual framework. This type of research does not offer conclusive answers to research questions but lays the groundwork for more conclusive research in the future (Adler & Clark, 2015). An example of exploratory research could be the study of patients’ experiences of a new treatment through unstructured interviews and/or participant observations of their daily routines. A research strategy that is typically applied in exploratory studies is grounded theory (discussed in chapter 6.3.).

Descriptive research aims to provide a very detailed, and accurate, picture of a particular group, event, process, or situation with which the researcher is already familiar. The focus is merely on describing what is being studied without seeking to explain it. Descriptive studies often rely on the collection of large volumes of quantitative data. A population census is a typical example of descriptive research that maps the socioeconomic and cultural profile of a particular country by gathering information on every single person living within it, whilst revealing changes over time (Adler & Clark, 2015).

Explanatory research is not limited to describing what happens but is primarily aimed at explaining why it happens (building theory). Many consider this type of research as the only one that is truly “scientific”. It is much more powerful than descriptive research; the ability to explain is a core defining element of science and what differentiates “observation” from “knowledge”. Descriptive studies enjoy lower status within the scientific community than studies which aim to explain (Punch, 2005). An example of explanatory research was a series of experiments conducted by American professor Stanley Milgram in the 1960s who examined why people were ready to obey unreasonable requests from authority figures even if these were utterly unjust or cruel (Adler & Clark, 2015).

In practice, social research does not fall neatly into one category of research or another. It usually embodies different purposes and levels of investigation. For example, an exploratory study may also be used to describe the social phenomenon under investigation as well as to provide tentative explanations of it (Walter, 2019).

Theory and research

Thus far, we have referred to the concept of “theory” in a rather intuitive way, without explicitly defining it. But what exactly is theory? Put simply, theory is the attempt to explain an observable event, with the explanation being couched in more abstract terms than those used to describe it (Punch, 2005). A good example illustrating the process of theory development is presented by Field (2009). Let’s say you have noticed that your cat climbs up and stares at the TV when it is showing birds flying about but not when jellyfish are on. Your curious mind will probably urge you to come up with a plausible explanation of this behavioural pattern. You could say that fast-moving birds spark your cat’s prey drive making her jump to the screen unlike slow-moving jellyfish that fail to catch her attention. For this explanation to acquire the value of a theory it must be phrased more abstractly so that it covers a wider range of situations (other than birds, jellyfish, or just your cat). So, you could perhaps say that swiftly moving images on TV spark a cat’s hunting instinct – especially if there is an auditory component to them such as chirping – and make it cling to the screen.

The process just described is known as theory generation or inductive reasoning. That is, one starts with specific observations and infers a general conclusion from them. In the previous example, you first observed (generated data about) your pet, you then analysed those data to identify a general pattern of behaviour, and after that, you developed an explanation of that pattern (a theory explaining initial observations). It is important to highlight that theories are probabilistic in nature which means that they rarely have universal applications; they provide explanations only in terms of tendencies in groups rather than predicting accurately individual conduct. They are also dynamic in character; they are expected to change and improve, whilst they may be overturned by completely new evidence or perspectives (Black, 1999).

But how do we test the “correctness” of a theory once we have generated it? This is a process known as theory verification or deductive reasoning in which one starts from a general conclusion and applies it to specific cases or situations to see if it applies. So, once a theory has been generated, we can make predictions about what is likely to happen under certain circumstances according to what the theory maintains. These predictions are called “hypotheses”. To test our hypotheses, we need to collect new empirical data and check whether they fit our initial predictions (theory) (Black, 1999).

Let’s expand on Field’s (2009) hypothetical example of “cats watching TV”. One logical prediction (hypothesis) deduced from our proposed theory might be that if a given film is played in the homes of a randomly selected sample of cats, the majority will start watching attentively once fast-moving images appear on the screen while they will remain rather apathetic during slow motion scenes. To test this hypothesis, we can ask cat owners to keep notes of their cat’s behaviour during the film by filling in a structured observation schedule. Data gathered in this way may or may not support our initial hypothesis. If most cats behave in the predicted way, we can assert that our theory is verified. Yet, if the data contradict our hypothesis, we will inevitably conclude that our theory is “falsified” or “disproven”, or that it needs to be modified to become a better fit for the data.

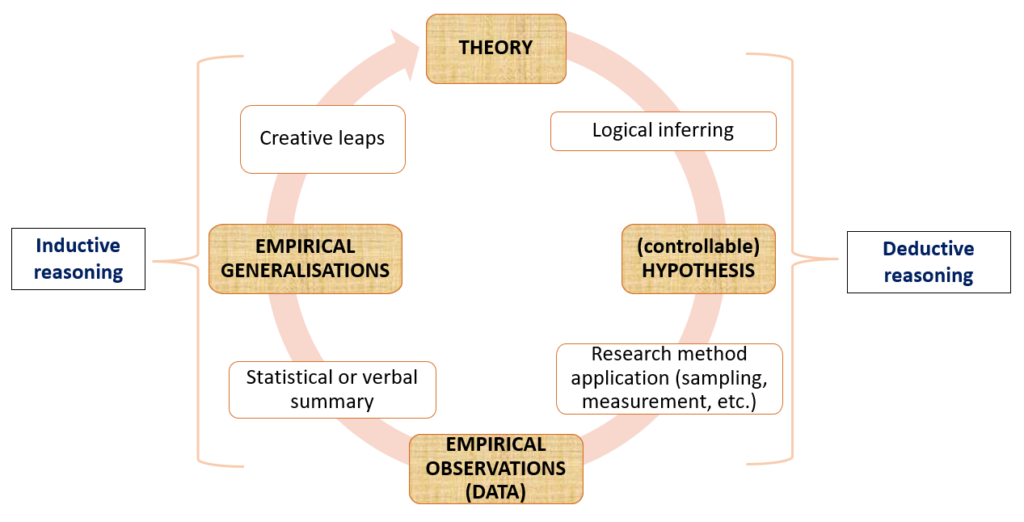

In practice, research follows a cyclical path of inductive-deductive reasoning as shown in Wallace’s (1971) circular model of science depicted in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3. Wallace’s circular model of science (adapted from Adler & Clark, 2015)

According to this model, a theory produces specific hypotheses which the scientist must test by generating empirical data through carefully planned processes (research methods). These data are then analysed to check whether they bear out initial predictions, and ultimately, to determine if the theory provides a useful explanation of the phenomenon under study or if it requires revision. In either case, the scientist is ready to generate new hypotheses for testing and s/he may go through the cycle several times. Our observational study of cat behaviour might produce data that shows cats being attracted to fast-moving TV images only the first time these appear on the screen and that, once a cat gets used to them, she loses interest. This can lead to the modification of our theory so that it accounts for how new a given TV showing is for the cat, thus, initiating a new inductive-deductive cycle.

The philosophical foundations of social research

So far, social research and the “scientific method” have been discussed in a relatively unproblematic way. Yet, there is a crucial aspect of doing “science” that has been blatantly disregarded so far: the researcher’s philosophy of the world and of humans’ relation to it. This philosophy manifests itself when one answers two basic questions:

- What is reality?

- How do we know reality?

The first question is an ontological one; it refers to the nature of being (existence). The second one is an epistemological question concerned with the human mind’s relation to reality, i.e. can we know things, and if yes, how do we come to know these things, and what exactly do we know? There are different ontological and epistemological positions in relation to the above questions – known as paradigms[1]– which give rise to diverse approaches (or methodologies) to doing social research. An extensive presentation of these is beyond the scope of this book. We will limit our discussion here to two paradigmatic stances that largely shape contemporary thinking about the world and how humans relate to, and come to know, it: positivism and post-modernism (Holliday 2016; Punch, 2005).

Positivism holds that social reality is an objective entity existing independently of human perception. It also asserts that this reality is inherently ordered despite its seemingly chaotic surface. That is, social phenomena are governed by universal cause-and-effect laws in exactly the same way as natural phenomena are. Hence, human behaviour, as well as the behaviour of human systems, can be predicted and controlled if these laws are discovered. For positivists, researchers can decipher these laws through systematic (sense-based) observations of their social environment. Care must be taken so that these observations are not distorted by the observer’s prejudices but that they represent pure and accurate “facts” about the world as it really is (Coyle, 2016; Sarafidou, 2011). Positivism has been criticised for failing to acknowledge that no human representation of reality can be truly objective (valid). The social “facts” that positivists claim to provide are themselves products of human consciousness; they do not exist “out there”, in the objective world. In response to this criticism, an “amended” post-positivist philosophy emerged asserting that, whilst researchers need to pursue objectivity, they must recognise the inevitable influence of human biases. Post-positivism retains the idea of an objective reality, external to the researcher, but holds that this reality cannot be accurately represented; one can only come to know it through informed guesses or conjectures. Post-positivist researchers aim at achieving intersubjectivity (instead of objectivity) by comparing their results to those of others in an attempt to identify points of agreement about what this objective reality might be (Holliday, 2016; Adler & Clark, 2015).

Post-modernism emerged as a reaction to positivism. It straightforwardly rejected the destructive illusion that there is an external, objective reality, knowable through the application of the supposedly impersonal norms and procedures of “science”. Contrary to this nomothetic view, postmodern researchers assert that no meaningful social worlds can be discovered “out there” until they have been constructed by people. They maintain that reality cannot be studied independently of human sense-making, because what we call “reality” is the very product of human action, interaction, history, and culture. The meaning people give to their circumstances is what explains why they do whatever they do. Hence, postmodern researchers are not particularly concerned with identifying cause-and-effect relationships between variables in order to explain (or predict) observed phenomena, but they focus on uncovering people’s subjective interpretations of these phenomena and the ways in which they actively shape these. In other words, humans are considered active makers of their social worlds rather than passive pawns governed by universal laws (Holliday, 2016; Punch, 2005).[2]

From a post-modernist perspective, it is not just research participants who construct their social settings; researchers come to re-construct those settings in the course of their studies. They bring to the setting a certain ideology and a given language which bind what they “see” and what they “say”. The language researchers use does not just describe (in a transparent way) the reality being studied, but it re-creates this reality. Language is a creator of meaning; it conditions the data generated in a study by imposing limits on what can be said and how it can be said. Furthermore, the social setting is moulded during a study as the researcher interacts, and forms relationships, with participants. So the researcher and the researched co-construct the social setting, which is “doomed” to change every time a study is conducted. This is why “reflexivity” in research acquires importance in post-modern thinking; researchers are expected to identify in what ways their actions, interactions, and interpretative frameworks influence the settings being studied, their research processes, and their outcomes. Post-modernist philosophy is closely associated with other paradigms (such as relativism, interpretivism, social constructionism, or feminism) and could be viewed as an overarching term that encompasses all the others (Coyle 2016; Holliday, 2016; Punch, 2005).

Let’s take an example to illustrate how the two paradigms affect the way social research is conducted. A positivist researcher who wants to explore the smoking of marijuana by teenage boys living in a working class neighbourhood of a big city will probably aim to identify the (independent) factors associated with a high probability of an adolescent getting involved in this illegal activity by carefully operationalising the variables of interest, developing appropriate instruments to measure these variables, collecting (mainly numerical) data from large representative samples of young boys, and statistically analysing these to determine significant associations or causal links. The ultimate objective might be to propose policy measures for reducing (controlling) this “negative” (unwanted) behaviour. On the other hand, a researcher with a post-modernist perspective will probably focus on generating rich (non-numerical) data – in the form of talk, text, images, sound, etc. – by immersing herself (or himself) in a given working class neighbourhood for an extended period of time so that s/he can uncover the meanings that teenage boys attach to the act of smoking marijuana and the non-visible ways in which it shapes their lives. Uncovering what “smoking marijuana” means to research participants will ultimately explain why they do it. Such a study may not be concerned with putting forward any suggestions for policy and practice to “amend” (control) boys’ behaviour.

Quantitative and qualitative research

From the above discussion, one may infer that quantitative research is always associated with positivistic thinking, whereas qualitative research is grounded on a post-modernist philosophy. Such conclusion is neither entirely correct, nor necessarily wrong. Even though it applies to many cases, quantitative research may also be part of a post-modernist approach to doing social science, whereas qualitative research may be applied and interpreted in a positivistic way (Adler & Clark, 2015).

Technically speaking, what differentiates quantitative from qualitative research is not so much their philosophical underpinnings but the type of data they generate and use. Put simply, quantitative methods involve the generation and analysis of data that can be codified into numbers and subjected to statistical analysis, whereas qualitative research involves the generation of data that are not numerical (e.g. sounds, images, text, etc.) and which are analysed as such, using methods other than statistics (Walter, 2019; Jensen & Laurie, 2016; Adler & Clark, 2015).

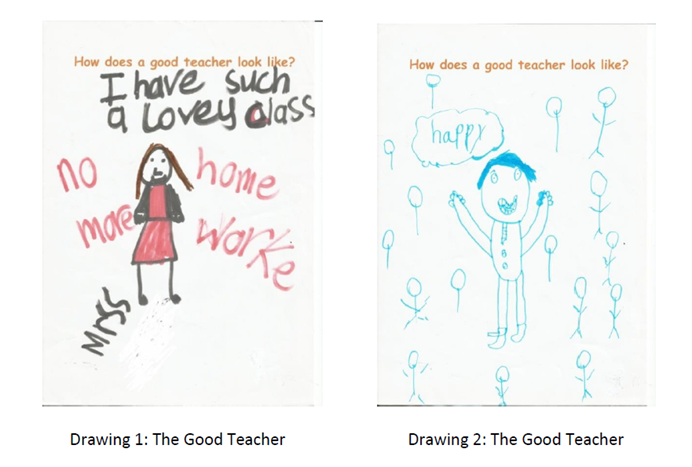

Furthermore, quantitative research allows the generation of data from large representative samples of people, giving room for generalisations to be made to entire populations. Common quantitative methods of data generation include self-completion questionnaires, structured interviews, or structured observations (see chapter 5.2.). Qualitative research mainly aims at gaining deep understandings of people’s experiences in specific contexts, a process that requires rich contextual (but not large-scale) data. It focuses on smaller units of people to draw the meanings and understandings they attach to social phenomena. Common qualitative methods of data generation include unstructured interviews, focus groups, participant observations, taking photographs, creating drawings, etc. (discussed in chapter 6.2.) (Walter, 2019; Jensen & Laurie, 2016)

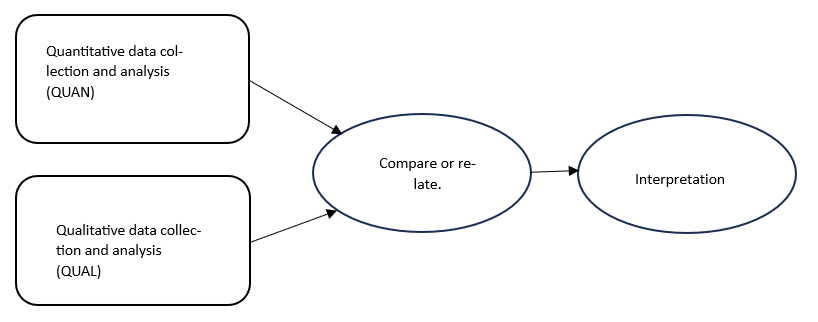

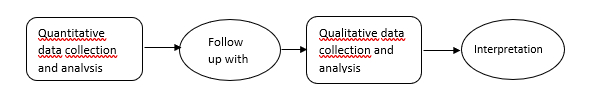

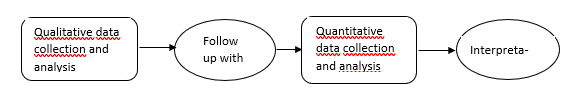

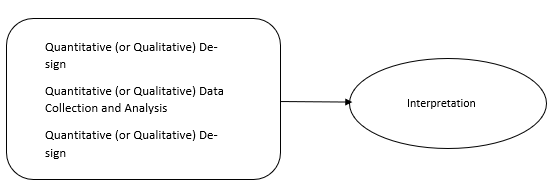

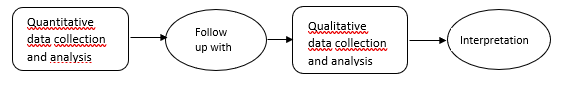

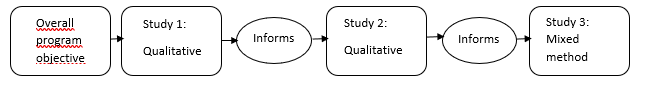

As both approaches have strengths and weaknesses, many studies combine these to get the best out of each one, leading to what is known as “mixed methods designs” (discussed in Chapter 8).

Concluding remarks

This chapter described social research as a natural (almost spontaneous) process of human learning about the social world. It showed that the main components of such everyday life research – i.e. focus, collection of empirical data, analysis of this data, explanation, logic, a systematic approach, and accounting for previous knowledge – coincide with the core defining features of the so-called “scientific method”. Yet, for research to be considered “scientific”, it must also adhere to a set of additional standards agreed upon, and shared by, an international community of established researchers within which certain power relationships and micropolitics also exist. Throughout the chapter, it has become apparent that researching the social (constructed) world is often more complicated than researching the physical world, because social phenomena are interwoven with human belief systems and different people may understand these in completely different ways. In an attempt to identify different types of social research, we referred to basic research, which aims at generating knowledge for knowledge’s sake, and to applied research which is conducted with action in mind. The organic relationship between research and theory was also examined, highlighting the complementary processes of theory generation (inductive reasoning) and theory verification (deductive reasoning). Furthermore, the importance of philosophy in guiding social research was emphasised and two opposing paradigms were presented, namely positivism and postmodernism. Positivism asserts that social reality is an objective entity existing independently of human perception; hence, researchers must depict this reality as accurately as possible through systematic observations, taking care so that these observations are not distorted by their prejudices. Post-modernism, on the other hand, rejects the positivistic assumption that there is an external, objective reality, maintaining that reality cannot be studied independently of human sense-making. Finally, the chapter differentiated quantitative from qualitative research, by asserting that quantitative methods involve the use of data that can be codified into numbers, whereas qualitative research involves the use of non-numerical data.

Self-assessment questions/quizzes

- What is the “scientific method” and how does it differ from everyday life research? Give a practical example.

- Choose one journalist’s report that is currently topical on the media. Write down what characteristics make it a piece of journalism and what you would need to do differently if you wanted to research the same topic empirically.

- We hear, or read, about many different studies on a daily basis (from newspapers, professional bulletins, our bosses, friends, TV programmes, etc.). What are we supposed to believe, and how can we judge if the results are useful?

- Explain the difference between basic and applied social research by giving a specific example.

- Let’s assume you wanted to study the new types of romantic relationships that have been developed as a result of the increasing use of the internet and online dating. What type of research would that be? Exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory? Justify your answer.

- In what ways does your intended doctoral research have the postmodern features described in this chapter?

- Which of the following would be regarded as qualitative data?

- Interview transcripts

- Social media posts

- Photographs

- All of the above

- Cyber bullying at work is a growing threat to employee job satisfaction. Researchers want to find out why people do this and how they feel about it. The primary purpose of such a study is:

- Description

- Prediction

- Exploration

- Explanation

- Which of the following is a form of research typically conducted by managers and other professionals to address issues in their organisations and/or professional practice?

- Action research

- Basic research

- Professional research

- Predictive research

References

Adler, E. S., & Clark, R. (2015). An invitation to social research: How it’s done (5th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Bakken, S. (2019). The journey to transparency, reproducibility, and replicability. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 26(3), 185–187.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics. London: Sage Publications.

Coyle (2016). Introduction to qualitative psychological research. In E. Lyons & A. Coyle (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data in psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 9-30). London: Sage.

Field (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Gannon, F. (2004). Experts, truth, and scepticism. EMBO Reports, 5(12), 1103.

Holliday, A. (2016). Doing and writing qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

Jensen, E. A., & Laurie, C. (2016). Doing real research: A practical guide to social research. London: Sage Publications.

Northouse, P. G. (2016). Leadership: Theory & practice (7th ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Punch, K. F. (2005). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Sarafidou, G. O. (2011). Συνάρθρωση ποσοτικών & ποιοτικών προσεγγίσεων: Η εμπειρική έρευνα [Reconciliation of quantitative & qualitative approaches: The empirical research]. Athens: Gutenberg.

Wallace, W. (1971). The logic of science in sociology. Chicago: Aldine.

Walter, M. (2019). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Further Reading

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2022). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. London: Sage Publications.

Jha, A. (2024). Social research methodology: Qualitative and quantitative designs. Oxon: Routledge.

Malone, T (2023). Research methods in social science. Wilmington: American Academic Publisher.

[1]Punch (2005, p. 27) defines paradigm as “a set of assumptions about the social world, and about what constitute proper techniques and topics for inquiry… a view of how science should be done.”

[2]We could say that, for post-modernists, reality can only be lived (not observed) and one can come to know reality only through living. By living reality, one continually acts upon, and transforms, it.

Social research strategies, research design, planning a re-search project and formulating research questions and research hypoth-eses

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of the study of this chapter the students will be able to understand the notions of social research strategies and research design, to plan a research project and to formulate research questions and research hypotheses. By comprehending and identifying the basic features of the two basic research strategies (qualitative and quantitative) and the basic steps of planning and implementing a research project, students will be able to plan their own research project and state their research question(s) and hypotheses.

Research strategies

As already mentioned, social research is the scientific study of society. It examines attitudes, beliefs, trends, stratification, and the rules of society and seeks to provide answers to or even solve social problems. Based on existing approaches, social research can be considered the systematic process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting information and data to prove a hypothesis or answer a specific question that may help understand a social phenomenon. Social research is applied to a wide range of disciplines, such as sociology, political science, psychology, economics and the media (Bryman, 2012; Armenakis, 2021; Babbie, 2021).

By the term research strategy, we mean a general orientation to the conduction of social research (Bryman, 2012:35). In the realm of social research there are two basic strategies to follow (and their combination): quantitative research strategy, through the implementation of quantitative research methods, and qualitative research strategy, through the implementation of qualitative research methods (Adler & Clark, 2011; Armenakis, 2021, Tsigganou et al., 2018; Babbie, 2021).

Quantitative research is a research strategy that emphasizes quantification in the collection and analysis of data and that entails a deductive approach to the relationship between theory and research, in which the emphasis is placed on the testing of theories; has incorporated the practices and norms of the natural scientific model and of positivism in particular; and embodies a view of social reality as an external, objective reality.

By contrast, qualitative research is a research strategy that usually emphasizes words rather than quantification in the collection and analysis of data and that predominantly emphasizes an inductive approach to the relationship between theory and research, in which the emphasis is placed on the generation of theories. Qualitative research puts an emphasis on the ways in which individuals interpret their social world and considers social reality as a constantly shifting emergent property of individuals’ creation (Bryman, 2012:36).

Quantitative and qualitative research represent different research strategies. Each carries with it differences in terms of the role of theory, epistemological issues, and ontological concerns. However, the distinction is not an absolute one: studies that have the broad characteristics of one research strategy may have a characteristic of the other (Bryman, 2012:37). In addition, one could actually pinpoint several “common” characteristics that permeate both strategies:

- They are both theory-related -literature review is a necessary step for both of them.

- They require the formulation of research questions and/or research hypotheses.

- It is necessary to collect data, although with different research tools and methods.

- After the collection of data, the next step for both strategies is the process and analysis of the gathered information through different analytical tools.

- And, of course, in both cases the last steps of the research are the presentation of the results and the relevant discussion/conclusions (Tsigganou et al., 2018).

As it has become obvious, theory is important to the social researcher because it provides a meaningful ground for the research that is being conducted, since it provides a framework within which social phenomena can be understood and the research findings can be interpreted (Bryman, 2012:20; Adler & Clark, 2011; Armenakis, 2021; Babbie, 2021). Deductive theory represents the most common view of the nature of the relationship between theory and social research. The researcher, on the basis of what is known about in a particular domain and of theoretical considerations in relation to that domain, deduces a hypothesis (or hypotheses) that must then be subjected to empirical scrutiny. In order to do that, the researcher must “translate” the hypothesis into operational terms. This means that the social scientist needs to specify how data can be collected in relation to the concepts that make up the hypothesis. Theory and the hypotheses deduced from it come first and drive the process of gathering data. In the discussion of her/his basic findings (after the research has been conducted) the researcher is engaged in a process of induction, as (s)he infers the implications of her or his findings for the theory. This deductive approach is usually associated with quantitative research (Bryman, 2012:24; Babbie, 2021).

Deductive process appears very linear-one step follows the other in a clear, logical sequence (Tsigganou et al., 2018). However, there are many instances where this is not the case: a researcher’s view of the theory or literature may change as a result of the analysis of the collected data; new theoretical ideas or findings may be published by others before the researcher has generated her/his findings, or, the relevance of a set of data for a theory may become apparent after the data have been collected (Bryman, 2012:25), especially in exploratory research (Armenakis, 2021; Babbie, 2021).

An alternative position is to view theory as something that occurs after the collection and analysis of some or all the data associated with a project (Bryman, 2012:24), the so-called inductive approach. The inductive approach emphasizes moving from more specific kinds of statements (usually about observations) to more general ones and is, therefore, a process called inductive reasoning. Many social scientists engage in research to develop or build theories about some aspect of social life that has previously been under-researched. Theory that is derived from data in this fashion is sometimes called grounded theory (Adler & Clark, 2011:33). According to the inductive rationale, theory is the outcome of research. In other words, the process of induction involves drawing generalizable inferences out of observations (Bryman, 2012:26; Armenakis, 2021).

To a large extent, deductive and inductive strategies are possibly better thought of as tendencies rather than as a clear-cut distinction (Bryman, 2012:27; Adler & Clark, 2011:32). It is probably most useful to think of the real interaction between theory and research as involving a perpetual flow of theory building into theory testing, and back again (Adler & Clark, 2011:34).

Choices of research strategy, design, or method have to serve answering the specific research question(s) under scrutiny. If we are interested in teasing out the relative importance of a number of different causes of a social phenomenon, it is quite likely that a quantitative strategy will fit our needs. Alternatively, if we are interested in the world views of members of a certain social group, a qualitative research strategy that is sensitive to how participants interpret their social world may be more appropriate. If a researcher is interested in a topic on which no or virtually no research has been done in the past, the quantitative strategy may be difficult to employ, because there is little prior literature from which to draw leads. A more exploratory stance may be preferable, and, in this connection, qualitative research may serve the researcher’s needs better, since it is typically associated with the generation rather than the testing of theory and with a relatively unstructured approach to the research process.

Factors influencing the choice of a research strategy

A factor influencing the choice of the different research strategies and the subsequent implementation of the research method(s) is the values of the researcher. Values reflect either the personal beliefs or the feelings of a researcher. According to the Weberian rationale on the “neutrality” of the researcher, we would expect that social scientists should be value free and “objective” in their research. Such a view is held with less and less frequency among social scientists nowadays, since there is a growing recognition that it is not feasible to keep the personal values “out of the research”. These values can intrude at any or all stages of social research (e.g., choice of research area, formulation of research question, interpretation of data, conclusions). It is quite common, for example, for researchers working within a qualitative research strategy, and in particular when they use participant observation or very intensive interviewing, to develop a close affinity with the people whom they study to the extent that they find it difficult to disentangle their stance as social scientists from their subjects’ perspective (Bryman, 2012). Nowadays, most researchers acknowledge that research cannot be value free, but one must ensure that values do not dominate the scientific implementation of the research method(s), even though values can serve as motivation for the conduction of specific research projects (e.g., in feminist studies/feminist social research) (Bryman, 2012:39-40).

Another dimension influencing the decision on the research strategy to be followed has to do with the nature of the topic and of the people being investigated. For example, if the researcher needs to engage with individuals or groups involved in illegal activities, such as gang violence or drug dealing, (s)he would preferably use a qualitative strategy where there is an opportunity to gain the confidence of the subjects of the investigation or even in some cases not reveal their identity as researchers, albeit with ethical dilemmas, as we shall discuss in the next chapter of the educational material at hand.

Research methods are associated with different kinds of research design. The latter represents a structure that guides the execution of a research method and the analysis of the subsequent data, it actually guides the implementation of the decided strategy (Bryman, 2012:45). A research method is a technique for collecting and/or analyzing data. It can involve a specific research instrument/tool, such as a self-completion questionnaire or an interview guide, or participant observation whereby the researcher listens to and watches others, or a technique for analyzing the data gathered such as thematic analysis, (critical) discourse analysis etc. (Bryman, 2012; Babbie, 2021).

All in all, social research is a coming-together of the ideal and the feasible (Bryman, 2012:41), and the researcher has to make her/his strategic and on-the-spot decisions in order to overcome any obstacles that might encounter in her/his way. On top of that, one should bear in mind that there is no “perfect” research strategy or research project. Thus, any researcher should be aware and acknowledge the limitations of her/his research.

Evaluation of social research

Three of the most prominent criteria for the evaluation of social research are reliability, replication, and validity. Reliability is concerned with the question of whether the results of a study are repeatable. The term is commonly used in relation to the question of whether the measures that are devised for concepts in the social sciences (such as poverty, racial prejudice, deskilling, religious orthodoxy) are consistent. Reliability is particularly at issue in connection with quantitative research. Ιf, for example, IQ tests were found to fluctuate, so that people’s IQ scores were often wildly different when administered on two or more occasions, we would be concerned about it as a measure. We would consider it an unreliable measure (Bryman, 2012:46).

The idea of reliability is very close to replicability (though in social research replication is very rare as a practice). There may be a number of different reasons for trying to replicate the findings of a research, such as a feeling that the original results do not match other related evidence (counter-intuitive results). In order for replication to take place, a study must be replicable, hence the research procedures followed must be documented in great detail (Bryman, 2012:47).

A further and in many ways the most important criterion of research is validity. Validity is concerned with the integrity of the conclusions that are generated from a piece of research and can be divided in three ‘categories”: measurement validity, internal validity, and external validity.

Measurement validity applies primarily to quantitative research and to the search for measures of social scientific concepts. Measurement validity is also often referred to as construct validity. Essentially, it is to do with the question of whether a measure that is devised of a concept really does reflect the concept that it is supposed to be denoting. Does the IQ test really measure variations in intelligence? Measurement validity is related to reliability: if a measure of a concept is unreliable, it simply cannot be providing a valid measure of the concept in question (Bryman, 2012:47).

Internal validity is concerned with the question of whether a conclusion that incorporates a causal relationship between two or more variables is valid. If we suggest that x causes y, can we be sure that it is x that is responsible for variation in y and not something else that is producing an apparent causal relationship? In discussing issues of causality, it is common to refer to the factor that has a causal impact as the independent (control) variable and the effect as the dependent (interest) variable. Thus, internal validity raises the question: how confident can we be that the independent variable really is at least in part responsible for the variation that has been identified in the dependent variable[1]? (Bryman, 2012:47; Armenakis, 2021). We will further elaborate on that relationship in the quantitative research section, and more specifically when we discuss the statistical tests.

External validity is concerned with the question of whether the results of a study can be generalized beyond the specific research context (Bryman, 2012:47; Babbie, 2021).

Various kinds of research

Research projects, according to their scopes can be classified in several categories:

- Exploratory research constitutes groundbreaking research on a relatively unstudied topic or in a new under-researched area (Adler & Clark, 2011:13) (e.g., researching the effects of quarantine due to a pandemic).

- Descriptive research, a researcher describes groups, activities, situations, or events, with a focus on structure, attitudes, or behavior. Researchers who do descriptive studies typically know something about the topic under study before they collect their data, so the intended outcome is a relatively accurate and precise picture. Examples of descriptive studies include the kinds of polls done during political election campaigns, which are intended to describe how voters intend to vote (Adler & Clark, 2011:14).

- Analytical–Explanatory-Interpretive, research to analyze, explain and interpret “cause-effect” relationships that permeate the characteristics of a situation, a subject, or a phenomenon (e.g., research on the reasons for using social media) (Armenakis, 2021).

- Basic/fundamental research is designed to add to our fundamental understanding and knowledge of the social world regardless of practical or immediate implications (Adler & Clark, 2011:11; Armenakis, 2021) (e.g., the ideological orientation of Media outlets).

[1] Dependent variable, a variable that a researcher sees as being affected or influenced by another variable (contrast with independent variable). Independent variable, a variable that a researcher sees as affecting or influencing another variable (contrast with dependent variable) (Adler & Clark, 2011:24).

The fact that two variables are associated with each other doesn’t necessarily mean that change in one variable causes change in another variable (Adler & Clark, 2011:25).

[1] Dependent variable, a variable that a researcher sees as being affected or influenced by another variable (contrast with independent variable). Independent variable, a variable that a researcher sees as affecting or influencing another variable (contrast with dependent variable) (Adler & Clark, 2011:24).

The fact that two variables are associated with each other doesn’t necessarily mean that change in one variable causes change in another variable (Adler & Clark, 2011:25).

- Applied research is intended to be useful in the immediate future and to suggest action or increase effectiveness in some area (Adler & Clark, 2011:11, 382; Armenakis, 2021) (e.g., which measures do citizens prefer to implement in terms of tackling climate change).

- Evaluation research is research designed to assess the impacts of programs, policies, or legal changes. It often focuses on whether a program or policy has succeeded in effecting intended or planned change, and when such successes are found, the program or policy explains the change (Adler & Clark, 2011:16, 383). The most common evaluation research is outcome evaluation, which is also called impact or summative analysis. This kind of evaluation seeks to estimate the effects of a treatment, program, law, or policy and thereby determine its utility. These research projects typically begin with the question “Does the program accomplish its goals?” or the hypothesis “The program or intervention (Adler & Clark, 2011:383) (independent variable) has a positive effect on the program’s objectives or planned outcome (dependent variable).”

- Cross sectional research is research that is conducted only once at a specific point in time (Armenakis, 2021).

- Longitudinal research is research repeatedly conducted at regular or irregular intervals (e.g., ESS- European Social Survey, EVS- European Values Survey, Eurobarometer) (Armenakis, 2021).

A research plan (steps to conduct a research)

There is a range of possible ways to choose a research project, such as personal scientific interest, interest in improving the researcher’s knowledge and skills on a specific issue, theory, research literature, puzzles/theoretical debates, new developments in society, social problems, discussions with colleagues, accessibility of data, willingness to collaborate with competent authorities or research populations, eagerness to resolve issues that may rise in relation to the uncertainty of the existence / collection of data (Tsigganou et al., 2018; Bryman, 2012:88).

In any case, not all ideas, no matter what has triggered them, are adequate to become research projects. Thus, a researcher should try to avoid extremely large “panoptic” subjects, common issues that have been already extensively scrutinized, issues for which there is no research material or access to the material is extremely difficult or impossible (e.g., research that has to do with content that can be found only in archives, very technical and highly specialized topics for which it is difficult to gather a significant number of participants/units of analysis (sample), issues whose course depends on the completion of other research projects (especially when our time-frame is short), issues that might violate the codes of ethics and ethics of social research (Tsigganou et al., 2018).

The basic steps towards the implementation of a research include (in most cases) the following:

- an overview of the theory through the review of the relevant literature,

- the formulation of research questions and research hypotheses,

- the data collection,

- the data analysis and interpretation (seeking to answer the research questions and hypotheses)

- and the discussion including the limitations of the research and new research ideas (Tsigganou et al., 2018).

Research questions-Research hypotheses

Usually, researchers begin their research with a research question, or a question about one or more topics that can be answered through research (Adler & Clark, 2011:2). Whereas research projects that have explanatory or evaluation purposes typically begin with one or more hypotheses, most exploratory and some descriptive projects start with research questions (Adler & Clark, 2011:73). Research questions should be clear, in the sense of being intelligible. Research questions are similar to hypotheses, except that a hypothesis presents an expectation about the way two or more variables are related, but a research question does not. Both research questions and hypotheses can be “cutting edge” and explore new areas of study, can seek to fill gaps in existing knowledge, or can involve rechecking things that we already have evidence of (Tsigganou et al., 2018).

Several steps are needed to turn a research question into a researchable question, a question that is feasible to answer through research. The first step is to narrow down the broad area of interest into something that’s manageable. You can’t study everything connected to cell phones, for example, but you could study the effect of these phones on family relationships. You can’t study all age groups, but you could study a few. You might not be able to study people in many communities, but you could study one or two. You might not be able to study dozens of behaviors and attitudes and how they change over time, but you could study some current attitudes and behaviors. While there are many research questions that could be asked, one possible researchable question is: In the community in which I live, how does cell phone use affect parent-child relationships; more specifically, how does the use of cell phones affect parents’ and adolescents’ attempts to maintain and resist parental authority? (Adler & Clark, 2011:88) The research questions we choose should be related to one another. If they are not, our research will probably lack focus and we may not make as clear a contribution to understanding as would be the case if research questions were connected (Bryman, 2012:90).

In brief terms, research questions:

- Should be researchable—that is, they should allow you to do research in relation to them. This means that they should not be formulated in terms that are so abstract that they cannot be converted into researchable terms.

- Should have some connection(s) with established theory and research. This means that there should be a literature on which you can draw to help illuminate how your research questions should be approached. Even if you find a topic that has been scarcely addressed by social scientists, it is unlikely that there will be no relevant literature (for example, on related or parallel topics).

- Should be linked to each other. Unrelated research questions are unlikely to be acceptable, since you should be developing an argument in your dissertation. You could not very readily construct a single argument in relation to unrelated research questions.

- Should be able to make an original contribution -however small- to the topic.

- Should be neither too broad (so that you would need a massive research project to study them), nor too narrow (so that you cannot make a reasonably significant contribution to your area of study) (Bryman, 2012:90; Tsigganou et al., 2018).

On their behalf, research hypotheses aim to interpret the relationship between theory (as described/presented in the essay) and research findings. Research hypotheses describe the questions, making judgments about their answer (according to the theory). Consequently, the results of a research are intended to verify or not the assessments made by research hypotheses. Rejecting a research hypothesis does not necessarily mean that it is wrong or that the implementation of the research is wrong. It may mean that a theoretical approach does not (fully) apply/correspond to the case of our research (Tsigganou et al., 2018).

Research hypothesis assessment starts with a theory or a claim about a specific population parameter. In order to examine if the claim will be confirmed by the research results, we state a pair of research hypotheses:

- The null/working hypothesis (H0) usually represents the existing situation as described in our theory. This assumption is true to the point that we have sufficient evidence to reach the opposite conclusion. Whenever a null working hypothesis is specified, an alternative hypothesis is also specified and must be true if the null is false (the two hypotheses are mutually exclusive).

- The alternative hypothesis (H1/HA) is the opposite of null hypothesis and covers all other cases not covered by zero (Tsigganou et al., 2018). Thus, the pair of research hypotheses is “exhaustive” in the sense that either the H0 or H1/HA will be true and there is no other (third) option.

It is not necessary to describe both hypotheses (null and alternative) in the context of a research text.

Let’s assume that we want to conduct research on the TV viewing habits of Greek people. According to our theory “the average TV viewing time in Europe for 2017 was 2 hours and 56 minutes”. Having this information as a reference point, we could formulate our null and alternative hypotheses as follows:

(H0): Based on the data available for television viewing in Europe, we expect the average viewing time in Greece to be 2 hours and 56 minutes (so μ = 2 hours and 56 minutes).

(H1/HA): Average view time isn’t 2 hours and 56 minutes (so μ ≠ 2 hours 56 minutes).

Conclusion

The choice of research strategy(ies) and the subsequent research method(s) to be implemented are the first steps towards the implementation of a research project. On top of that, the researcher should be able to formulate adequate research questions that actually “drive” the whole research procedure, and research hypotheses (if needed) that operationalize the theoretical background -needed in both qualitative and quantitative research- and provide the basic directions/parameters of study to the research project.

Choices of research strategy, design, or method have to serve answering the specific research question(s) under scrutiny. If we are interested in teasing out the relative importance of a number of different causes of a social phenomenon, it is quite likely that a quantitative strategy will fit our needs. Alternatively, if we are interested in the world views of members of a certain social group, a qualitative research strategy that is sensitive to how participants interpret their social world may be more appropriate.

Exercise

You are interested in finding out which teaching methods are more “attractive” to university students. How would you formulate your main research question? What research strategy would you follow to answer your main research question? Which are the basic steps you would implement towards the completion of your research project?

Questions

- What is the difference between a research strategy and a research method?

- Name some of the similarities and differences between the qualitative and quantitative research strategies.

- Which are the two basic characteristics of the H0 and H1/HA?

- In which ways as the working hypotheses related to theory?

- Which are the different categories of validity?

- Which are the main aims of exploratory and descriptive research?

References

Adler, S. E. and Clark R. (2011). An Invitation to Social Research: How It’s Done (4th Ed.). Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Armenakis, A. (2021). Research Methods. Learning Material for Postgraduate students of the Department of Communication and Media Studies of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Babbie, E. R. (2021). The Practice of Social Research (15th Ed.). Cengage.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods (4th Ed.). Oxford University Press.

Tsigganou, I., Iliou, K., Fellas, K. N, Balourdos, D. and Giakoumatos, S. (2018). Research Methods. Learning Material for the National Center for Public Administration and Local Government.

Further Study

Bailey, K.D. (1978). Methods of social research. Free Press.

Crotty, Μ. (1998) The foundations of social research. Sage Publications.

Flick, U. (2009). An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 4th Ed. Sage.

Gray, D. E. (2004). Doing Research in the Real World. Sage Publications.

Kumar, R. (1999). Research methodology. A step-by-step guide for beginners. Sage Publications.

Mertens, D. (1998). Research methods in education and psychology: integrating diversity with quantitative & qualitative approaches. Sage Publications.

Pickering, M. (2008). Research Methods for Cultural Studies. Edinburgh University Press.

Theory and research: Literature review- Writing up social research

This chapter examines various methods of documenting social research to offer fundamental concepts for structuring our own written work, particularly if tasked with producing a dissertation.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to understand the importance of writing, particularly effective writing, in social research; identify how quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research are written, with examples; recognize the expectations and conventions of writing for academic audiences by identifying the elements of a research report and the various formats in which research might be written.

Introduction

Regardless of the size of a research project, it’s easy to forget that writing it up is a critical part of the process. Writing not only presents our findings but is also vital for persuading our audience of the research’s validity and significance. If findings of studies are not appropriately presented, all the various approaches mentioned in the previous sections will serve nothing. This means that proficient English, or whatever is the usual language one uses, is a minimum requirement for a good social report. When we use extremely complicated terms and constructions, communication is hampered (Babbie, 2021).

Scientific reports have several purposes. According to Bryman (2016), first, our report must clearly convey a specific set of data and ideas, providing enough detail for others to evaluate it thoroughly. We should view our report as a contribution to the collective body of scientific knowledge. While maintaining humility, we must also recognize that our research adds to the broader understanding of social behavior. Lastly, our report should inspire and guide future investigations.

Bryman (2016) emphasizes on the following points:

On time

With the important tasks of gathering and analyzing one’s data, writing is often overlooked and undervalued. While writing up one’s findings cannot occur until after the data have been analyzed, it is advisable to begin writing much earlier. Getting a head start on writing can help the researcher clearly organize the research questions, set the literature in context, and avoid the common mistake of underestimating how long it takes to make revisions to the work. Procrastination is one of the factors that lead to writing at the last minute, which is not ideal. It is very crucial for success to write carefully and early since a full presentation of the results and conclusions of the research is needed to give credit to the study.

Persuasion

Researchers need to persuade readers that their conclusions are believable, important, and plausible. It is not sufficient to present findings and fail to convince the audience of their importance. Writing up research involves more than reporting findings and conclusions; relevant literature needs to be integrated, the research process has to be accounted for, and the analysis has to be described.

Language

There should be no discriminatory, sexist, or disablist language in researcher’s writing.

Feedback

Seek as much feedback on your writing as possible, particularly from your supervisor – make sure to give him/her enough time to comment thoughtfully. You may also want to ask peers, but your supervisor’s feedback will likely be the richest.

Key Dissertation Components

Title Page

This page includes your institutional requirements as it may also contain the dissertation title, the name of the author, the degree, and the date of submission.

Acknowledgements

These are credits for individuals who may have guided or assisted you in your work-for example, gatekeepers, colleagues who may have commented on the work, or your supervisor for guidance and advice.

List of Contents

A standard list of your dissertation’s chapters and sections.

Abstract

A summary of the whole dissertation, including your questions, methodology, results and conclusion.

Introduction